The life and legacy of Tupac Shakur is a story that has been told on several occasions, but not quite like Allen Hughes tells it with the FX docuseries Dear Mama. In five, powerful episodes, this award-winning director delves deeply into the psyche of the iconic rapper, but also examines the woman that made it all possible – Afeni Shakur.

In the 27 years since his death, Tupac’s legend has risen to monumental heights, but the journey of Afeni is one that hasn’t been highlighted in the magnitude that it is with Dear Mama. “To know Afeni is to know her son,” Hughes says. “The revolutionary mind, the passion, the intelligence of Tupac, most of that we can attribute to his mother.” Through interviews with family, friends, colleagues and the like, this series gives viewers a better understanding of its central figures, for better or worse.

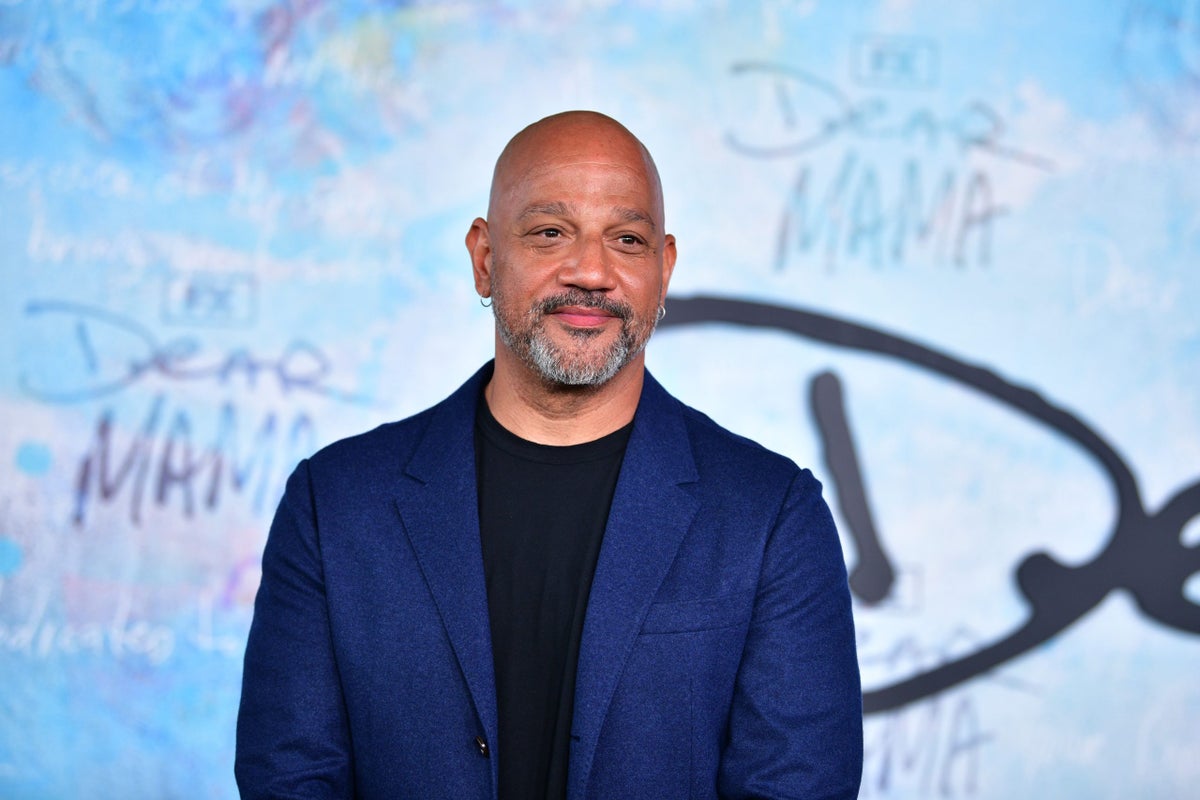

In the aftermath of Dear Mama’s release, Hughes spoke with ESSENCE about the legacy of Tupac and Afeni Shakur, how he provided a fresh take on a popular story, the cultural importance of this series, and more.

ESSENCE: There are so many documentaries, works, and books on Tupac. So there’s just so much information on him. How are you able to compile this series by giving us so much new information without making it redundant?

Allen Hughes: Well, I think the first thing is starting with his mother, using her as the prism to see his journey through. We added a fresh perspective and voices, just by virtue of that approach alone. Also, my whole disposition of coming into something like this is just complete empathy and curiosity.

When you have your ears and your heart open, with whoever I’m sitting down with, whether it’s Afeni’s sister and Tupac’s aunt Glo, or a former Panther, or a cousin, or a best friend, I just engage in those interviews like an audience member. So they see me reacting, they see me navigating what they’re saying, because the genuine curiosity is there, and I think you get other insights because of that approach.

And in my technique, too, you see me leave the error in the interview so you can see the subtext with the subjects, as well. So I think that’s why. I think that’s why there’s new stuff in this piece, because it’s also 27 years later after his passing, and a lot of people are in a different place, and have healed somewhat to a place of perspective that they just didn’t have 15 years ago.

I’m glad you said that – since he did pass almost 30 years ago, why did you all decide to put this series out now as pertaining to 10 years ago or 10 years later? What was it about now that was so important?

Well, I was approached about it over four years ago. It wasn’t even on my agenda, but once I agreed to do it and figured out how to do it, and what I wanted to do, and the estate and the family graciously agreed to my request, it just became right. For me, I’m like, “look at our times, look at what’s been happening since 2016. Look how this country has gone backwards 50 years.”

There’s no better time to chronicle this journey of Tupac and Afeni, and what it actually stood for, what he actually stood for, what his mother stood for – civil rights, human rights, women’s rights – all that stuff. Fighting your oppressor. The government stuff that they were dealing with as an organization back then, those Panthers, and how they were decimated by the FBI, I’m like, “No time like the present to examine all that stuff.”

So in making Afeni the core of this series, was that part of the idea from the beginning, or did that materialize as you were compiling information?

That was my number one request. I said, “If I’m going to do this, it’s got to be a dual narrative as much about Afeni as it is about him.” I wanted to explore this because I had heard that they’re very similar, and a lot of his personality traits, a lot of their family and friends described them as twins. I was like, “Well, that’s interesting – what does that mean?” And I knew what a highly intelligent individual she was and how ahead of her time she was in her thinking, and I just wanted to explore that. So that was number one. That wasn’t a thing that we discovered along the way we wanted to do. That’s something we started out wanting to do.

Afeni and Tupac, they were both great people, but they also had their imperfections, as we all do. Were you hesitant at all to highlight some of the flaws that they had in the film, while maintaining that balance of the positive traits that they had?

I think if you’re going to do any of these things the right way, and if you’re going to humanize somebody, it’s got to be the good, the bad, and the uncomfortable, or the unnerving, or some say the ugly, right? And as long as you paint a balanced portrait, especially of figures as powerful as Afeni and Tupac, people will still embrace and love them.

In fact, I’ve learned they become closer to them when they see the fallibilities and the imperfections because they see themselves in them, and they’re not just this mythical perfect creature. In fact, they become more mythical, because I always say when you demystify them, people connect to them and then you can soar right back out into the universe again, and it gets bigger. So, I think it’s part of my approach and the documentaries I’ve done, particularly this one, is to really evenly humanize it all, because I think it’s the most unassuming way to inspire people because they see themselves in it.

Earlier, you spoke about talking to Tupac’s family and loved ones, they said that he and Afeni had a lot of similarities. When you were doing this film, what similarities did you recognize between those two?

I think Watani says it in the film, he goes, “Both charismatic. Both took charge of a room when they walked into it. Both are short-tempered. Both highly articulate, highly intelligent. Both very well read, very well studied.” I can go on and on and on. I think the only difference between the two of them is that I don’t know if Afeni had the sense of humor Tupac had. She was a serious woman, and that would be the only difference between the two of them. But they both were natural-born leaders, as well.

And you actually had a relationship with Tupac. You knew him. When you were doing this film, did it change your perception of him at all? Or did it just heighten what you already felt?

It definitely changed my perception of him and I have a deep compassion for him now that I just didn’t have before, because I just didn’t know. Outside of our personal kerfuffle and our personal relationship, which actually was wonderful for the most part. And sometimes challenging, and then it got violent. But I’m not one to sit there and hold grudges.

And at the end, he was very apologetic about what happened. So I wasn’t one sitting over here harboring any weird feelings. I didn’t understand a lot about him – where’s the paranoia come from? Where’s the erratic behavior come from? What was up with that last 11 months of his life? I didn’t understand how that connected to the first 24 years of his life.

So, there were all these misunderstandings that I think a lot of us had, that once I found out what he was born into, the inherited trauma, the expectation the movement had for him, the way poverty can just decimate your psyche. And you see it in Dear Mama, I just have a tremendous amount of compassion for him now, and I understand it. I get it now.

What do you think was Afeni’s biggest influence on her son?

I think to question authority and consummate activism. To speak truth to power. I think almost to a fault. Also, when you don’t have a father in the house and you have an activist mother, women are more in touch with their emotions. Men suppress their emotions.

Fathers teach us, “Yo, you shouldn’t say that right now. Maybe you should bring it down right now. You shouldn’t reveal your…” Fathers are the ones that usually teach that. So when you’re raised by a single mother who’s an activist and a radical revolutionary, you’re popping off a lot more than the average dude’s going to pop off, just by virtue of who raised you and her being a strong-minded female because they just don’t have that censor that men tend to force upon themselves. So that’s a weird, strange alchemy he had because of her.

When people finish the last episode, what do you want them to take from the series? And what do you want them to remember about Afeni?

I mean, she says it at the end. She’s singing it during that speech. We people who believe in freedom cannot rest until we’re free – and I’m paraphrasing. At the end, you see her talking about the fight for freedom, and it’s an eternal struggle. We left on that note for a reason. Her son’s gone and she’s out speaking, and she’s singing the “Sweet Honey In The Rock” song about the struggle for freedom.

In 2016, something happened in our culture, our politics, and in our leadership where you were like, “Wow, we’re going back to the ’50s with this brand of racism. And it’s just out loud now, it’s going pop.” One of the Black Panther veterans pulled me aside along the journey and said, “This is an eternal struggle. It’s never over. It’s never won. Don’t think that we’ve achieved anything other than small little victories that we have to actually maintain and be vigilant about.” As in the case of Roe vs. Wade, when women thought they had the right, you blink, it’s gone.

So I think that Afeni reminds us at the end of Dear Mama, of that eternal struggle and that eternal fight for racial justice, freedom, and human rights. It’s a never-ending fight, and it’s heartbreaking to think about it that way. She said it to him and he said it to us, “I don’t think I’ll see freedom in my lifetime,” but it’s our part to play the part in that chain that is going to lead to freedom down the line.

In my lifetime, I was naive enough to go, “Oh no, I’m going to experience this.” When Barack Obama was voted into office, I wasn’t naive enough to think that because we had a black president, racism was over. I was naive enough to think that by the time I’m 80, a lot of this will be done within our country, and that’s just not true.